Choosing or tuning a PC for gaming, content creation, AI workloads, or even everyday productivity often leads to a confusing question: what’s the difference between dedicated and shared GPU memory, and how much of each do you actually need? This post walks through the concepts, architecture, performance implications, and real‑world recommendations so you can make informed decisions about hardware and settings.

At a high level, dedicated GPU memory (VRAM) is high‑bandwidth, graphics‑specialized memory that lives on the graphics card itself and is used exclusively by the GPU, while shared GPU memory is a portion of your system RAM that the GPU borrows when it runs out of VRAM or when there is no dedicated VRAM at all. Dedicated memory is much faster and more predictable, which is why it dominates performance‑critical tasks like modern gaming and GPU compute, and why shared memory is best viewed as a safety net rather than a performance feature.

GPU Memory Basics

What is GPU memory, conceptually?

The GPU needs a fast workspace to store and access data such as:

- Framebuffers (the images to be displayed on screen)

- Textures, meshes, shaders, and geometry

- Intermediate buffers used in rendering or compute (e.g., G‑buffers, shadow maps, or neural network tensors)

This workspace is GPU memory, and it comes in two main forms on consumer systems:

- Dedicated GPU memory (VRAM): Special high‑bandwidth memory chips directly attached to a discrete GPU.

- Shared GPU memory: Regular system RAM that the GPU can use over the system memory bus when needed.

The key trade‑off is bandwidth and latency vs flexibility and cost. Dedicated VRAM is faster but fixed and more expensive. Shared memory is slower but flexible and cheaper to implement (especially for integrated GPUs).

Dedicated GPU Memory (VRAM)

What is dedicated GPU memory?

Dedicated GPU memory, commonly called VRAM (Video RAM), is a separate pool of memory physically located on the graphics card or GPU package, directly wired to the GPU. Modern VRAM uses technologies like GDDR5, GDDR6, or HBM (High Bandwidth Memory) that are optimized for high throughput and low latency for graphics workloads.

This memory is:

- Exclusive to the GPU – not shared with the CPU or other devices.

- High bandwidth, often hundreds of GB/s, thanks to wide buses and fast GDDR/HBM chips.

- Fixed in capacity – 4 GB, 8 GB, 12 GB, 24 GB, etc., and cannot be upgraded without replacing the GPU.

Because VRAM is directly attached and tuned for the GPU’s access patterns, it can feed many more pixels, higher‑resolution textures, and more complex shaders than system RAM at the same capacity.

Why is VRAM so much faster than system RAM for GPU tasks?

Several architectural reasons:

- Physical proximity: VRAM is placed very close to the GPU die, shortening signal paths and reducing latency.

- Wide memory interface: GPUs use wide buses (e.g., 128‑bit, 256‑bit, 320‑bit, 384‑bit, 8192‑bit for HBM) to move huge amounts of data per clock cycle.

- Specialized memory types: GDDR and HBM are designed for high bandwidth, not general‑purpose latency characteristics, making them ideal for large, streaming graphics workloads.

- Dedicated role: VRAM is not contending with the CPU for access, unlike system RAM that must serve many devices.

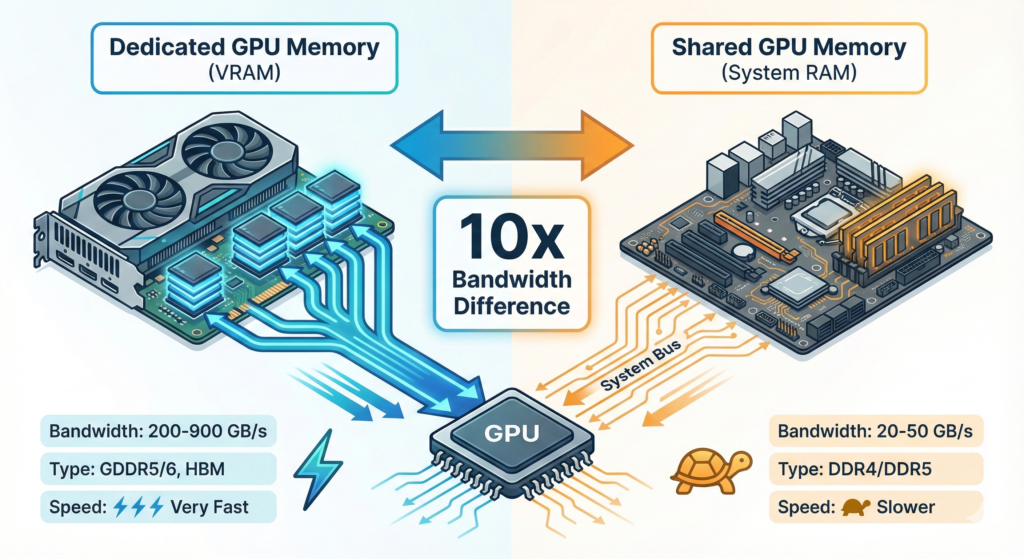

As a result, VRAM bandwidth can be 4–10× (or more) higher than dual‑channel DDR system memory, and some educators frame it as “dozens of times faster in practice” for GPU access compared to shared RAM.

VRAM vs system RAM: different roles

Even though both are “memory”, VRAM and system RAM serve distinct purposes:

- VRAM (dedicated GPU memory):

- Holds graphics‑specific data (textures, framebuffers, render targets)

- Optimized for high throughput to the GPU

- Directly impacts frame rate, image quality, and resolution

- System RAM:

This separation is intentional: it prevents GPU bandwidth needs from starving the CPU and vice versa, and lets each memory type be specialized.

Shared GPU Memory

What is shared GPU memory?

Shared GPU memory is a portion of system RAM that the GPU can use as if it were video memory. This appears in tools like Windows Task Manager as “Shared GPU memory”. Practically:

- On integrated GPUs, all graphics memory is shared system RAM, with perhaps a small reserved “dedicated” block.

- On discrete GPUs, shared memory is used as a fallback when VRAM is full or for certain staging operations.

Windows, for example:

- Reserves up to about half of the system RAM as potential shared GPU memory for the graphics subsystem.

- Dynamically migrates resources between dedicated VRAM and shared RAM to avoid outright crashes when VRAM is exhausted.

This design prioritizes stability (avoiding crashes and blue screens) over performance.

Shared memory in integrated vs discrete GPUs

Integrated GPUs (iGPUs / APUs):

- Built into the CPU package and have no dedicated VRAM; they always use system RAM as graphics memory.

- The BIOS or firmware often lets you reserve a minimum amount (e.g., 128 MB, 512 MB, 1–2 GB) as “dedicated” for the iGPU, but it still resides in system RAM.

- Their performance is heavily limited by system memory bandwidth and configuration (single vs dual channel).

Discrete GPUs:

- Have their own VRAM and prefer to use it first.

- Use shared system memory only when VRAM is exhausted or for specific driver‑level reasons; when this happens, performance usually drops significantly.

- Many games and GPU‑intensive apps only count VRAM, not shared memory, when checking minimum video memory requirements, because shared memory is too slow to be meaningful.

How shared GPU memory works in Windows

On Windows, Task Manager’s GPU section shows:

- Dedicated GPU memory: true VRAM on the GPU (or reserved region in shared systems)

- Shared GPU memory: a pool of system RAM that can be used by the GPU

- GPU memory total: sum of both

However:

This keeps the system running but can severely hurt performance, especially with high‑bandwidth workloads like modern 3D games or large AI models.

Shared GPU memory is not a real VRAM extension; it’s a safety buffer to keep apps from crashing.

When VRAM is full, Windows and the display driver will:

Evict less‑used GPU resources from VRAM to shared system RAM

Pull them back when needed, over the much slower system bus

Dedicated vs Shared GPU Memory: Core Differences

Architectural differences

| Aspect | Dedicated GPU Memory (VRAM) | Shared GPU Memory (System RAM used by GPU) |

|---|---|---|

| Physical location | On the GPU card/package | On the motherboard with the CPU |

| Memory type | GDDR5/6, HBM, etc. | DDR4/DDR5 (general system RAM) |

| Bandwidth & latency | Very high bandwidth, low latency for GPU | Much lower bandwidth, higher latency for GPU |

| Exclusivity | Used only by GPU | Shared between GPU, CPU, OS, and other devices |

| Capacity control | Fixed by GPU model | Depends on total system RAM and OS/BIOS allocation |

| Primary use | Textures, framebuffers, real‑time rendering, GPU compute | Fallback when VRAM is full; primary storage for iGPUs |

| Performance impact | Directly drives graphics quality & frame rate | Often bottlenecked, significant performance hit when used |

| Upgradability | Only by upgrading GPU | Indirectly by adding system RAM |

These structural differences explain why VRAM capacity and bandwidth are key specs for gaming and GPU‑heavy workloads, while large shared pools are not a substitute for inadequate VRAM.

Performance implications

Dedicated VRAM performance benefits:

- Handles high‑resolution textures and large framebuffers without thrashing.

- Enables higher resolutions (1440p, 4K) and more complex effects (ray tracing, high‑res shadows).

- Maintains stable frame rates because data stays in high‑bandwidth memory rather than constantly moving over the system bus.

Shared memory performance drawbacks:

- Lower bandwidth: dual‑channel DDR4/DDR5 provides only a fraction of the bandwidth of modern GDDR or HBM.

- Contention: the same RAM is used by CPU, OS, and apps; heavy CPU workload can starve the GPU and vice versa.

- Latency and migration overhead: moving data between VRAM and shared RAM adds extra latency and bus traffic, which can produce stutters and FPS drops.

- Less predictable performance: OS scheduling, other running applications, and background services can all affect available bandwidth and latency.

Consequently, most games and GPU‑intensive software treat shared memory as “better than crashing, worse than everything else”.

Integrated Graphics, APUs, and Unified Memory Architectures

Integrated GPUs and shared memory

Integrated GPUs (iGPUs) are built into the CPU package and do not have separate VRAM. They use system RAM as their graphics memory, typically within a Unified Memory Architecture (UMA) where CPU and GPU share a single memory pool.

In such systems:

- The BIOS or firmware can reserve a minimum amount of RAM for graphics (e.g., 256 MB, 512 MB, 2 GB), which appears as “dedicated” in some OS tools but still lives in system RAM.

- The OS can allow the iGPU to borrow additional RAM dynamically beyond this reserved amount.

- Memory bandwidth is the primary bottleneck for iGPU performance, not core count in many cases.

Upgrading from single‑channel to dual‑channel RAM, and increasing RAM speed (e.g., from 2666 MHz to 3200–6000+ MHz) can substantially improve iGPU performance, because it raises the available bandwidth for both CPU and GPU.

APUs and future unified designs

APUs (Accelerated Processing Units), like AMD Ryzen chips with integrated graphics, are classic UMA designs. Their performance scales strongly with memory bandwidth:

- Single‑channel vs dual‑channel RAM can make a dramatic difference in FPS.

- Faster DDR generations (DDR5 vs DDR4) offer more bandwidth and thus better potential iGPU throughput.

Industry trends suggest more systems may move toward unified memory (especially in mobile and console‑like form factors) where high‑bandwidth memory is shared between CPU and GPU to reduce power, cost, and complexity. However, at the high end, discrete GPUs with large dedicated VRAM pools and technologies like HBM still dominate due to extreme bandwidth needs.

How Windows, Games, and Apps Treat Shared GPU Memory

Windows memory accounting and scheduling

Windows’ GPU memory reporting and management is designed with stability and responsiveness in mind:

- The OS and graphics drivers can migrate resources between VRAM and shared RAM as needed to keep foreground apps running.

- “Shared GPU memory” in Task Manager shows how much system RAM is available for GPU use, not how much has been permanently taken away.

- The Video Scheduler and driver decide which resources to keep on the GPU and which to evict to shared memory based on current workloads.

This dynamic behavior means:

- You cannot reliably “force” an app to use shared memory as a performance booster.

- You generally want to avoid hitting the point where shared memory is heavily used, as it typically signals VRAM pressure and impending performance penalties.

Why games focus on dedicated VRAM

Game developers usually specify minimum and recommended VRAM requirements (e.g., “6 GB VRAM required, 8 GB recommended”) for several reasons:

- Predictability: VRAM provides consistent high bandwidth, while shared RAM performance varies greatly by system configuration and workload.

- Compatibility: Relying on shared memory can produce inconsistent results, stuttering, and poor user experience on systems with slower RAM or heavy background load.

- Testing: It is practically impossible to validate every combination of shared vs dedicated memory across all users’ hardware.

Therefore, even if Task Manager shows a large “GPU memory total” (VRAM + shared), the game’s requirement usually only counts dedicated VRAM, and you should treat it that way when evaluating hardware.

Practical Scenarios and Recommendations

1. Gaming

For gaming, dedicated VRAM is far more important than shared memory:

- 1080p gaming: 4–8 GB of VRAM is typically enough for modern titles at reasonable settings.

- 1440p: 6–8 GB or more is recommended, especially with higher texture and quality settings.

- 4K or ultra textures: 8–12 GB or more may be needed for smooth performance in demanding titles.

If your GPU regularly runs out of VRAM:

- You’ll see stuttering, texture pop‑in, or hitching as data is moved between VRAM and shared RAM.

- Reducing texture quality, resolution, and certain effects can lower VRAM usage and avoid dependency on shared memory.

Upgrading to a GPU with more VRAM is usually more effective than relying on shared memory, even if you have a lot of system RAM.

2. Integrated graphics and light gaming

If you’re using integrated graphics (Intel UHD, Iris, AMD Radeon iGPU, etc.):

In this context:

- Increasing RAM speed and enabling dual channel can be as impactful as (or more than) simply increasing capacity.

- Reserving huge amounts of memory exclusively for the iGPU (e.g., 8–16 GB) rarely doubles performance; it simply ensures the GPU has room, but the bottleneck remains bandwidth.

For light esports or indie titles, a well‑configured iGPU with fast dual‑channel RAM can be adequate, but it still won’t compete with a mid‑range discrete GPU with its own VRAM.

3. Content creation and professional workloads

For workloads like video editing, 3D rendering, CAD, and AI inference, VRAM capacity and bandwidth are often critical:

- High‑resolution timelines, complex 3D scenes, and large neural networks can easily consume many gigabytes of VRAM.

- When VRAM is exhausted and the software falls back to shared memory, you may see:

Professional tools and GPU compute platforms are therefore usually paired with GPUs that have ample dedicated VRAM (12 GB, 16 GB, 24 GB, or more).

4. Everyday productivity and web browsing

For everyday workloads (web, office apps, streaming):

- GPU memory demands are modest; shared memory is usually more than sufficient, and modern integrated graphics handle these tasks well.

- In such scenarios, prioritize:

You don’t need a large amount of dedicated VRAM for basic productivity; the difference will be negligible compared to CPU and overall RAM capacity for these tasks.

Myths and Misconceptions About Shared GPU Memory

“I have 4 GB VRAM and 8 GB shared, so I effectively have 12 GB VRAM.”

This is misleading:

- The extra 8 GB is system RAM, accessed over a slower bus, and shared with everything else.

- Performance using that memory can be dramatically worse than using VRAM alone, especially in bandwidth‑heavy workloads like modern 3D games.

- Games that require 8 GB of VRAM typically cannot run optimally on 4 GB VRAM plus 8 GB shared; they are tuned expecting 8 GB of high‑bandwidth dedicated VRAM.

“I can fix GPU performance by just adding more system RAM.”

Adding system RAM:

- Helps overall system responsiveness and can reduce paging.

- Can improve integrated GPU performance to a point, especially if it enables dual‑channel mode or higher speeds.

- But it does not magically turn shared memory into VRAM; the fundamental bandwidth and architecture differences remain.

For discrete GPUs constrained by VRAM, a GPU upgrade, not a RAM upgrade, is usually the solution.

How to Check and Interpret Dedicated vs Shared Memory

On Windows:

- Open Task Manager → Performance → GPU:

- Dedicated GPU memory: your VRAM capacity (or reserved region on integrated systems).

- Shared GPU memory: maximum amount of system RAM that can be used for GPU tasks.

- GPU memory: combined total.

In practical terms:

- For discrete GPUs, focus on the dedicated GPU memory number when comparing to game or application requirements.

- For integrated GPUs, focus on:

Practical Buying and Configuration Tips

When to prioritize dedicated VRAM

You should prioritize a GPU with more dedicated VRAM if:

- You play modern AAA games at 1080p+ with high/ultra textures.

- You run 4K or multi‑monitor setups with high resolutions.

- You work with 3D content creation, video editing, CAD, or GPU compute.

- You experiment with AI models that have large memory footprints.

In these cases, VRAM is a primary performance driver, and shared memory is only a fallback.

When shared memory is “good enough.”

Shared GPU memory (especially via integrated graphics) can be “good enough” if:

- Your workload is mostly office apps, browsing, streaming, and light content.

- You only run light games or older titles at low settings.

- You value battery life, low noise, and compact form factors over raw performance.

In that situation, investing in more and faster system RAM (e.g., 16 GB dual‑channel DDR5) often makes more sense than buying a low‑end discrete GPU.

Conclusion

Dedicated GPU memory and shared GPU memory serve fundamentally different roles, and they are not interchangeable. Dedicated VRAM is a fast, specialized, exclusive resource that directly determines how well your system can handle modern games, complex 3D scenes, and GPU‑accelerated workloads. Shared GPU memory, by contrast, is just system RAM borrowed by the GPU, primarily to prevent crashes and extend functionality on integrated or memory‑constrained systems, but at a substantial performance cost when heavily used.

Comments